A Journey to Kenya

© 2013 The Rev. Dr. Martin M. Davis (Ph.D.)

All Nations Christian Church International

Recently I had the extraordinary opportunity to undertake a sixteen-day journey to western Kenya, where I was to participate in a series of teaching lectures for a large number of African pastors of various independent evangelical churches. This trip was to prove to be one of the greatest and one of the most difficult events of my life. It was a journey filled both with great opportunities for ministry and great personal challenges.

The Journey Begins

Departing Jackson, Mississippi, on a cool February morning, I shuttled to Dallas on a cramped, crowded plane so small I had to bend over to walk the aisle to reach my seat. Following a three-hour layover, I joined my travel partner, Dr. John Githiga, a native Kenyan now living in Amarillo, TX, who is Patriarch of All Nations Christian Church International, a trans-denominational, global fellowship of churches, ministries and denominations with more than one million members in over 60 countries. After a twenty-hour flight, which included a three-hour layover in London, we landed at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport in Nairobi, the capital of Kenya, around 9:30 P.M. local time.

After disembarking the British Airways jumbo jet that had carried us safely across the Sahara Desert, a vast sandy wasteland larger than the continental United States, the first thing I noticed as I entered the terminal at Nairobi was the smell—an exotic, spicy aroma that told me I was now far from home. The second thing I noticed was the heat. We had arrived in Kenya during the hottest month of the year. For the next several days I would perspire continually, day and night, in a country that not only lacked air conditioning but fans as well. The third thing I noticed was a seated figure enshrouded in a full berka, completely wrapped in black with nothing but a narrow slit over her eyes through which poked a pair of thick glasses. As her medieval attire and demeanour bespoke bondage and the concomitant loss of freedom and individuality, I silently gave thanks for the freedom that is integral to the gospel of Jesus Christ.

At the airport we were met by our driver, Gabriel, the nephew of my traveling partner. After loading our luggage into a small station wagon, we slowly squeezed through one of the omnipresent traffic jams of Nairobi and drove thirty-minutes through relatively dark streets to arrive near midnight at the Guest House of the Anglican Church of Kenya, located almost directly across the street from the Israeli Embassy. With barricaded streets patrolled byarmed guards with automatic weapons, we were on the “safest street in Nairobi.” After a late check-in, I found my room and immediately opened the windows in hopes of drawing even a slight breeze into the stifling heat. After unpacking what I needed for the night, and having had no sleep for 30 hours, I quickly fell asleep around 1 A.M., wet with perspiration and surrounded by a mosquito net that blocked any slight breeze that might enter the overly warm room, as security guards chatted noisily in the darkness just outside my wide-open windows.

On to Murang’a

The alarm on my cell phone woke me rudely at 6:00 A.M. After brushing my teeth, being careful not to drink the brownish-coloured water from the faucet, I got into the shower and, after a few minutes, discovered how to get the hot water on. After a reasonably comfortable shower beside a chest-high open window, I attempted to “dry off,” while simultaneously dripping with perspiration.

I had bought several new pairs of pants for this trip which my wife Sara had carefully folded and wrapped in plastic before packing them in a large suitcase so that they would not wrinkle. Wet with sweat, I put on a new pair of pants, finished dressing and headed for the dining room for breakfast. I was shocked to discover, however, that the dining room was warmer than my bedroom. All the windows were closed and, not only was there no air conditioning, as I had expected, there were no fans. I thought to remedy the situation with a glass of cold orange juice and cereal with cold milk. To my horror, I discovered that Kenyans prefer hot milk on their cornflakes! Surveying the few people in the dining room, I also discovered one of the many cultural differences I would find in Africa. Unlike most Americans from the Deep South, who do not hesitate to smile at strangers, Kenyans are reluctant to make eye-contact with strangers, for to do so is to invite danger. After room-temperature juice, hot, soggy cornflakes, and a few pieces of warm fruit, I went outside to find any breeze that might waft my way.

At 10:00 A.M., our driver, Gabriel, arrived at the guest house to take us to Murang’a, a small city about 50 miles north of Nairobi, where we were to conduct the first of three teaching conferences with pastors from a variety of churches and independent ministries. In Kenya, where the population is 80 per cent Christian, the Anglican Church of Kenya is the predominant denomination. Many Kenyan Christians, however, dissatisfied with staid formality and what they regard as “spiritual deadness,” have left the ACK and other mainline Protestant denominations in search of the spiritual vitality associated with less formal, more spiritually-vibrant “independent” churches and ministries. These churches and ministries, however, lack the financial and material resources of the mainline churches. It was to these materially poor but spiritually rich brothers and sisters in Christ that we had come to minister.

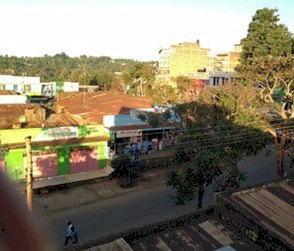

Late in the afternoon, we arrived at Queen’s Hotel in Murang’a, where the streets were alive with vendors hawking their wares, whether fruits and vegetables from nearby farms or CD’s blaring through giant speakers mounted atop parked cars. Like Nairobi, the weather in Murang’a was hot. We checked into the hotel, where I was relieved to find that my room had a flushing toilet and shower. I was disappointed, however, that the lack of ventilation rendered it almost uninhabitable except in the late evening and early morning. During our stay at Murang’a, I spent much time in T-shirt and shorts, spending the evenings sitting outside my room, perspiring as usual and trying to catch any breeze that drifted past. As a result of the heat, lack of sleep, strenuous physical demands and complete change of diet, I would lose fourteen pounds during our sixteen day journey to Kenya.

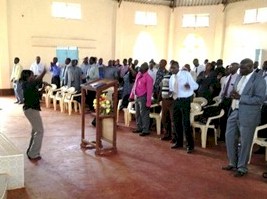

The next morning, after a breakfast of bread and fruit (I declined the hot soggy cornflakes), we dressed in full clerical attire and were soon picked up by Pastor James Mararo, a bishop of the Pentecostal Evangelical Fellowship of Africa, who drove us to his nearby church for the first day of a Spirit-filled conference attended by 120 pastors of various churches from the Murang’a area. Upon our arrival we were greeted by the pulsing sound of vibrant praise music emanating from the church sanctuary. As we entered the side door we saw dozens of pastors, male and female, singing, dancing and clapping in exuberant praise and adoration. Their energy seemed inexhaustible as they continued in one lengthy praise song after another. While the music went on, Dr. Githiga and I were invited to join Bishop James at the front of the congregation. Soon we too were clapping and swaying to the pulsing rhythm of the joyful sounds that filled the building, echoing from concrete walls and floors.

Following a substantial time of praise and worship, Dr. Githiga was introduced and received a warm, eager reception. The many pastors present listened with attentive appreciation to the first of a series of lectures on pastoral care. Midway through Dr. Githiga’s lecture, I found it necessary to visit the restroom, as I had been drinking copious amounts of bottled water in response to the hot, dusty climate of Murang’a. A courteous usher directed me to a wooden outhouse near the front left-hand corner of the church building. The rudimentary structure was divided into two small sections, one for “gents,” the other for “ladies.” As I entered the “gents’” side and pulled the plank door shut behind me, I was confronted by nothing more than a small concrete floor with a hole in the middle of it and a role of tissue suspended from the ceiling by a small rope. Because I found the experience something other than that to which I am accustomed, I resolved to reduce my water intake until we returned to the hotel late that afternoon.

After Dr. Githiga’s well-received presentation on pastoral care, I was invited to give the first of the many presentations—part sermon, part lecture—that I would give in Kenya on the foundational doctrine of the Christian faith: the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, beginning with God’s definitive self-revelation in Jesus Christ. I spoke in short phrases and sentences so that my words could be translated into Kiswahili, the inter-tribal language of east Africa, by Pastor Harrison Ndung´u, a native Kenyan fluent in English. During my presentation I was constantly challenged to find ways to reduce complex theological concepts to basic, ordinary language, not only because my words were being translated but also because my audience consisted of pastors rather than theologians. Later Pastor Harrison and I would begin initial discussions about a conjoint project involving a series of essays on Trinitarian-incarnational theology, which I would write for pastors and educated laity, and he, in turn, would translate into Kiswahili.

A Weekend in Ichichi

After two joyful days of praise, worship and teaching, the conference in Murang’a drew to a satisfactory close, and we departed for Ichichi, a small village in the Central Province of Kenya, nestled among the foothills of the lofty Aberdares Mountains, where Dr. Githiga spent his childhood. Here we were to meet with pastors of Vision Evangelistic Ministries (VEM).

On the first part of our journey to Ichichi, we enjoyed riding on relatively smooth paved roads. Soon, however, we left the “tarmac” and proceeded onto the first of many exceedingly rough and dusty roads that would slowly but eventually lead us to Ichichi. As we proceeded higher and deeper into the mountains, it seemed as if we were going backwards in time, as we left electric lines and other public utilities behind. We began to encounter women and children carrying heavy containers of water on their heads, water taken not from central water supplies or even wells but from the streams flowing through the many valleys hidden among the foothills. We passed carts pulled by donkeys, heavily laden with corn or sugar cane. We saw less fortunate women and boys, whose families could not afford a donkey, slowing climbing the poor mountain roads in sandaled feet, bent “double” under the massive, heavy loads of sugar cane, corn or fire wood they carried.

Like everywhere in Kenya, even the dusty roads in the remote mountains were lined with a steady parade of travellers, farmers and workers, walking to a neighbour’s home or to the nearest village, usually two or three miles away, to buy the few necessities they could afford. In the afternoons, school children scampered along the dusty steep roads, bound for home, dressed in their smart uniforms and carrying their books in their backpacks. As we slowly passed the children, I would wave from the left-hand front seat where I sat. Wide-eyed and mouths agape, they would inevitably point their fingers and gleefully shout in astonished surprise, “Mzungu!” (“White Man!”), for, as I was soon to learn, the regions where we would do part of our ministry were so remote and difficult to access, that these children, even teenagers, had never before seen a Caucasian.

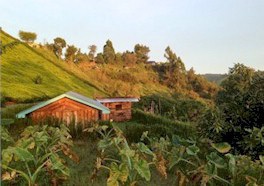

Our weekend sojourn in Ichichi was pleasant. For the first time since I had arrived in Kenya, I stopped perspiring, for the mountain air of the Aberdares foothills was cooler and fresher than the hot dusty air of Murang’a or Nairobi. We lodged in the homes of Dr. Githiga’s relatives, for these deeply devout mountain people were anxious to share their hospitality, especially with a Mzungu. Well-versed in scripture, they often referred to the passage in Genesis where Abraham welcomed the three strangers into his home, and they were determined to follow what they regarded as an important biblical example of hospitality to strangers. The homes where we stayed had no electricity; neither had they access to a central water supply. Most of the houses were small rectangular structures of wood, clay or brick with rusty tin roofs. Many of the people in the area drew their water from the cool streams that flowed at the foot of the slopes. Others collected rain water in huge tanks located alongside their rudimentary houses. For several days, my bath consisted of a small basin filled with water warmed over an open charcoal fire, a bar of soap and a wash cloth. After lightly scrubbing myself, I dipped my hands into the basin and splashed the warm water over my body to rinse off the pleasing, aromatic Kenyan soap.

During the evenings, the men gathered in small parlours lit only by kerosene lanterns to discuss important issues, including politics and theology. The 2013 presidential election was imminent and many feared a repetition of the violence that had accompanied the previous election five years earlier, when tribe had risen against tribe in a brief civil war that resulted in approximately twelve hundred dead and vast destruction of property and homes. Among these deeply devout villagers, the Bible was a subject of common discussion and the quotation of scripture was an integral, vital part of their conversation. During our first evening in Ichichi, we were entertained by Habel Githiga, a 75-year old retired priest and his wife “Mama Isaac,” who sang hymns for us in English, Kiswahili, and Kikuyu, the tribal language of Kenya’s largest ethnic group. In Kenya, married women with children are called “Mama,” coupled with the name of their first-born child.

The home of one of our hosts, Bishop William Githiga, his wife Helen, and their son Victor, sat high over a valley, whose steep slopes were draped in the lush green of tea plants, accented by long, slender, silvery trunks of eucalyptus trees and the broad arching leaves of heavily-laden banana plants. Standing on the front porch in the crisp, early morning, sipping a steaming cup of chai, I could see scattered upon the distant slopes tiny spots of colour among the tea plants, brightly-clothed workers stooped under large wicker baskets, bending over the steep slopes to pick the tea by hand, leaf by leaf, to be paid at the end of the day according to the number of kilograms they harvested. I could hear children laughing in the valley below, as they hurried along dusty roads to school, playing tag along the way. Beautiful, lush, peaceful and crime-free, the valleys around the remote village of Ichichi hid what is for most Westerners a forgotten time and place. Despite its lack of modern conveniences and notwithstanding the hard labour that marked life among the tea plants, I could not help envying the simplicity of life in these remote mountains, where neighbour still knew neighbour and ordinary life revolved around God, church and clan. It is little wonder that this tiny remote village in the Aberdares foothills has produced no less than seven bishops, including my travel partner, Dr. John Githiga.

On Sunday morning, Dr. Githiga and I were invited to be the guest speakers at the local VEM church. The service had started early and was well underway when we arrived. The hard-working villagers—men, women and children—were worshipping God in joyous praise, singing and clapping their hands, as energetic worship leaders rallied them on, accompanied by screeching microphones and the thump-thump-thump of the bass voice of the small but ever-present Yamaha digital piano that has become an integral part of Kenyan praise and worship music.

The church building was constructed of hand-made-brick and cement walls with wooden rafters, dusty concrete floors and hard wooden benches for pews. We were invited to sit behind the pulpit, facing the congregation, alongside the bishop and church elders, both male and female. After a gracious introduction, Dr. Githiga spoke on Jesus Christ as the “water of life,” paying careful attention to Jesus’ encounter with the Samaritan woman recorded in the Gospel of John. I spoke on the Holy Trinity as a communion or fellowship of love, whose gracious purpose for all humanity is revealed in history in the incarnation of Jesus Christ and the sending of the Holy Spirit.

After the service, we joined the church elders in a small meeting room for a lunch of rice, over which was poured a tasty stew of carrots, celery and bits of unspecified meat. The meal included chipati, the tortilla-like bread that accompanies all meals in Kenya. I gratefully ate several pieces of the thin bread patiently folded into layers, for I had learned that each piece was carefully rolled out by hand and slowly cooked, one piece at a time, over an open charcoal fire. With our meal we enjoyed chai, a combination of milk, water and the excellent tea for which Kenya is rightly famous.

After the meal, toothpicks were passed around as Dr. Githiga shared with the church elders his vision for All Nations Christian Church International. As he explained, ANCCI is not a denomination in the traditional sense; rather, we are a global fellowship of independent churches and ministries who share a common commitment to take the Gospel of Jesus Christ to “all nations” (Matthew 28:19, 20). As Dr. Githiga explained, ANCCI seeks to bring together, under the umbrella of historic apostolic succession, disparate and varied independent ministries scattered around the world, particularly in the Global South, so that they might share their strengths and gifts in a common effort to proclaim the Gospel of Jesus Christ to all humanity, especially the poor of the “third world.” As Dr. Githiga insisted, ANCCI does not seek to acquire property and material resources; rather, we seek to be a truly ecumenical, global communion rich in spiritual resources that we might share with others. In regard to the University of All Nations Christian Church International, Dr. Githiga reported that he has already brought together over a dozen doctoral-level faculty members who are willing to offer their training and expertise to those who otherwise cannot afford traditional biblical and theological training, particularly at the university and seminary level. He then appointed the first of several “regional coordinators,” who are responsible for recruiting students from Kenya for the University, that is, pastors and others who desire further biblical and theological training but whose lack of financial resources renders traditional pathways to learning impossible.

After the meeting, we visited several homes in the Ichichi area. As always we were received graciously and enthusiastically. I was honoured to learn that I was the first Mzungu ever to enter these homes. On one occasion, as we were walking down a rare, relatively smooth dirt road, I was deeply moved when one of my walking companions asked if the roads in my country (U.S.A.) were “as smooth as this one.” As visions of eight-lane interstates and crossovers stacked four high quickly flashed through my mind—a highway system I assumed she could not even imagine—I simply answered, “Yes, most of our roads are smooth.” As we continued our stroll along the dusty road, children ran from their houses, wide-eyed and mouths agape, to get a closer—but not too close!—look at the tall Mzungu that had come to their remote, isolated village. Later I was told that one elderly woman was astonished to see me walking along the road. “Do white men walk?” she had asked.

Nakuru and the Great Rift Valley

After our stay in the cool mountain air of Ichichi, we left early Monday morning for the second clergy conference, to be held in Nakuru, a city located in the vast Rift Valley of western Kenya. On our way, we stopped to enjoy a pleasant visit with the Vice Chancellor of St. Paul’s Theological College near Nairobi, where Dr. Githiga had been a former professor. We arrived late in the afternoon at the conference site to find the meeting well under way, as pastors of many churches worshipped together as one body in prayer and song. The conference in Nakuru was truly ecumenical, attended by pastors from a variety of independent ministries and denominations, who, as one pastor told us, had left the mainline churches of Kenya in order “to find the Holy Spirit.” Our message was enthusiastically received in Nakuru. The pastors present voiced their appreciation for the teachings we had given, while, at the same time, expressing their wish that we return to provide a more in-depth series of lectures on the essential doctrines of the Christian faith, particularly Christology (the doctrine of Jesus Christ) and Pneumatology (the doctrine of the Holy Spirit). At Nakuru, Dr. Githiga appointed another regional coordinator for ANCCI University, whose is responsible for linking pastors in the area who desire additional biblical and theological education with our organizational headquarters in Amarillo, Texas.

We remained one additional day in the area in order to tour the world-famous “game park” located around vast, beautiful Lake Nakuru. We spent several hours in the game reserve, guided by Pastor George Olendo, who operates a guide service in the area as a form of “tent-making,” so that he might serve his local congregation in the Rift Valley. In the game park, we were able to relax and simply be tourists, enjoying the variety of animals that inhabited the vast grasslands and acacia groves of the Rift Valley, including zebras, giraffes, cape buffalo, gazelles, impalas, a rhinoceros, and of course, the beautiful flamingos for which the lake is chiefly known.

The Remote Kisii Highlands

The next morning, we left for Kisii, a small city in western Kenya, lying just east and north of the borders of Uganda and Tanzania respectively. Our third and final conference in the remote Kisii Highlands would prove to be the most difficult and challenging of our time in Kenya.

Although the distance was only about 50 miles, the journey to Kisii took the entire day. Kenya is a developing country whose infrastructure is in various stages of completion. Beginning our journey on a new “tarmac” road under construction by the Chinese, we were disappointed when the smooth pavement soon ended and we began to encounter the unavoidable potholes that pockmark the older, much worn highways of Kenya. Despite the prohibitive road conditions, our driver, adamantly refusing to slow down, continually swerved left and right in a vain attempt to avoid the numerous potholes. We frequently found ourselves driving on the “wrong” side of the road as oncoming traffic, including large trucks, rapidly approached from the opposite direction, themselves swerving from side to side to avoid the potholes, while beeping their horns and flashing their headlights for us to get out of the way. As the journey continued, the road worsened as all remnants of pavement vanished and we were forced to grind slowly but reluctantly along dusty, washboard gravel roads toward Kisii, still many miles away. After what seemed an interminable length of pounding, banging, and coughing in the clouds of dust raised by the lines of trucks plowing the dirt highways of western Kenya, we encountered another stretch of newly paved road and accelerated toward Kisii, as a massive coral red sun set slowly over the Kericho district’s vast, rolling, lush-green tea plantations, so coveted by the British and continental Europeans during the colonial era of Kenya’s history.

After a long, tiring day of travel we arrived at our hotel in Kisii, too late for dinner, since the restaurant had already closed for the night. After checking in, we went to our rooms for a shower and a meal that consisted of one of the protein bars we had brought from home, washed down by a bottle of warm water. The shower in my room proved less than satisfactory, for the water was either scalding hot or ice cold. I soon learned to moderate the temperature by turning the hot water heater on and off with the switch located on the wall near the shower. Turning off the switch, I entered the warm stream long enough to get wet then switched the water heater back on before the water became too frigid. Matters were made worse by the shower shoes supplied by the hotel, for they continually stuck to the wet floor, making movement difficult. Eventually I was able to lather up, shampoo my dusty hair and even rinse off without either getting scalded or frozen. After my shower, I got into bed on top of the covers, because the room was overly warm, and, using my new iPhone as a sound machine to mask the street noise outside my window, soon fell asleep, despite the fact that my toes were protruding through the mosquito net draped around my short bed.

The next morning, I dressed and went to the hotel lobby to sit in the cool breezeway near the open double doors while awaiting Dr. Githiga. As I sat in a comfortable chair, catching the breeze, a young hotel employee entered, carrying what appeared to be a metal milk container. Out of friendly curiosity, I smiled and asked her what she was carrying. She replied, “It is milk for the restaurant. I got it from the cow three kilometers up the road.” When Dr. Githiga joined me, we went upstairs to an overly warm dining room with closed windows for a descent breakfast of fried eggs, link sausage, fruit and several cups of chai.

After breakfast, we were picked up by pastor Thomas Gwako to begin what would prove to be a tortuous journey to a rural church in the Kisii Highlands, twenty-four miles away. A short distance from our hotel, we encountered a large mob of people marching down the street, shouting and waving leafy green branches in their hands. As we slowly crept forward in the tangle of cars, trucks, motorcycles, donkey carts, and countless pedestrians scurrying across the busy street, we found ourselves surrounded by marchers, waving their branches and shouting political slogans in unison. We had inadvertently driven right into the middle of a large political rally ahead of Kenya’s hotly contested presidential election only a few days away.

After we were briefly carried along by a human wave of political devotees, the mob turned right into a public park and we were able to break free and continue on our way. Before we even reached the outskirts of the city, however, we were forced to pull to the side of the road, as the clutch burned out in the small car in which we were riding. After a short wait, another car appeared, and we switched vehicles in order to continue our journey into the remote mountainous back country where the conference was to take place. Soon, however, our difficulties continued to mount as the engine in the second car overheated, and we were forced to pull over a second time to the side of the road. Our driver got out, raised the “bonnet” (“hood”), and then silently walked away toward a nearby house. After knocking on the door of a small wooden hut with a rusty tin roof, he quickly returned with a huge aluminium teapot filled with water. After wrestling the radiator cap loose without burning himself, he poured in the water from the teapot and put the cap back onto the slowly cooling radiator. Then we drove to the nearest garage, where we obtained more water for the overheated engine, even storing a few spare jugs in the “boot” (“trunk”).

We finally left Kisii behind, travelling rapidly on a busy paved highway lined on either side by local farmers selling corn, potatoes, cabbages, carrots, and fruit from makeshift stands. Large numbers of vendors gathered at each stop sign along the way, hoping to make a sale, as they shoved bags of carrots or ears of corn through the lowered windows of our car. In addition to the vendors, the road was lined with pedestrians and bicyclists, as well as cows, sheep and donkeys, so that the roadsides were alive with constant movement and bustle. The traffic on the highway itself was heavy with cars, motorcycles, large trucks and countless mutatus, the over-crowded fourteen-passenger mini-vans that, for a few shillings, ferry cramped passengers from village to town. At each major intersection, a dozen or more young men waited on their motorcycles to offer rides to one (or more!) passengers for a mere shilling. One of the many contrasts that mark a developing country like Kenya became apparent as we dodged a slowly moving cart, heavily loaded with sugar cane and pulled by a reluctant, trudging donkey, whipped along by a screaming driver waving a rope on a short handle, only to be immediately passed ourselves by a stylish, brand-new Mercedes SUV bearing Kenya license plates.

Because there are no speed limits in Kenya and virtually no law enforcement on the highways, the roads, both paved and unpaved, are criss-crossed by speed bumps designed to slow down traffic. Intermittently laid across the road with no apparent pattern or design, these unmarked barriers are large enough to destroy the undercarriage of any vehicle whose driver fails to see them. Thus, we were constantly slowing down and speeding up as we made our way toward the Kisii Highlands. I was grateful for the twelve-hour, chewable raspberry Dramamine I had taken earlier that morning.

We soon left the tarmac and drove onto the first of the rough dirt roads that would take us to our mountain destination, still many miles away. Even on these rough dirt roads, we frequently encountered heavy trucks carrying their cargos to the many remote villages scattered every few miles throughout the mountains. Because the air was thick with dust raised by the trucks, Dr. Githiga was forced to tie his handkerchief around his head, creating a make-shift mask to cover his mouth and nose in order to breath. Later, at pastor Gwako’s suggestion, he would need to consume one litre of hot water to help clear his respiratory system of dust and reduce the risk of pneumonia.

As we journeyed deeper into the mountains, I saw women and children ascending the steep slopes from the stream far below the road, carrying heavy containers of water on their heads. Below me, I saw women washing clothes in the flowing streams, beating the garments clean on rocks and laying them out to dry in the sun. I saw another woman bent double under a heavy load of firewood as she slowly climbed the mountain road to her modest home.

The road conditions on the way to the Kisii Highlands were unlike anything I had ever encountered, even in remote Ichichi. Because of the large rocks and deep ruts in the roads, which frequently caused the bottom of the car to drag, we were often forced to travel at a “speed” of less than five miles per hour. Constantly we braced ourselves as the car rocked to and fro and swayed side to side in conditions more suitable for an army tank than a passenger car. At the base of one steep ascent, everyone except the driver was forced to exit the car and walk up the long hill that was too steep for the car’s four-cylinder engine. By the time we reached the top of the hill, we were out of breath. I was perspiring heavily and Dr. Githiga was growing faint as a result of his elevated blood sugar, for we had not eaten for several hours.

By late morning, we finally reached the remote mountain church, where about 70 pastors were already gathered in praise and worship. We got out of the dusty car, stiff from the beating we had taken on our rough journey from Kisii, and walked towards the church, surrounded by wide-eyed, gawking children from the local houses and farms. Delighted to see a Mzungu, many for the first time, these joyful youngsters were thrilled to have their picture made and “perform” for the camera. Shortly after we entered the church building, with its thick clay walls, dirt floor and tin roof, we were introduced and began our presentations, while the many pastors present rapidly jotted down copious notes.

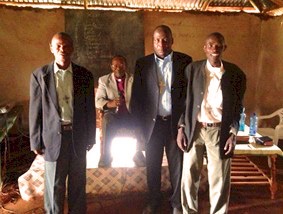

At the end of the first day of teaching, we joined many of the pastors and church elders for a late afternoon meal of rice, stew, chipati and several cups of chai. One of the pastors present was a young man who had been shot in the leg and slashed with a machete during the post-election violence that rocked Kenya in 2007. When his life was spared after he hid in the forest, he committed his life to Jesus Christ. As we relaxed with our fellow servants in a simple, darkening room with hard chairs and no electricity, Dr. Githiga invited the pastors present to bring themselves and their congregations under ANCCI’s umbrella of historic apostolic succession, explaining to them that they would become part of a global, ecumenical communion that emphasizes the commonalities among Christian brethren, while extending to its members freedom in doctrinal distinctives and styles of worship. After his invitation was received with approval, Dr. Githiga chose three men to be consecrated the following day as bishops in our global fellowship of churches and ministries. Each of these men already oversees a network of churches and pastors. One of them, Bishop Thomas Gwako, oversees seventeen churches located in Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi. Another is an evangelist from Tanzania who has planted many churches in his native country.

As the coral red sun was setting over Uganda, only a few miles to the west, we prepared for the long journey back to Kisii. I had a sense of foreboding when I saw two men using a bicycle pump to manually inflate the flattened right-rear tire of our car. Another used a hammer to repair the damaged rim on the spare. We began our journey on foot, for the car could not carry us up the steep path that led from the church to the road. As we trudged up the hillside, I quickened my pace in order to make speedier work of the one-fourth mile ascent. One of the many children who constantly followed us wherever we went, trekking right alongside me, commented, “You have a long ‘walk’ (i e., “stride”), Dr. Davis.”

After greeting several neighbours along the way, we finally reached the top of the long slope where the car and driver were patiently waiting. We began our return to Kisii quite slowly in order to avoid the large rocks and deep ruts that marked the remote, poorly maintained mountain roads. About five miles into the journey, we entered a small village, barely visible in the darkness, lit only by scattered kerosene lanterns, for there was no electricity. Suddenly, an animated conversation ensued among the other passengers and driver in Kiswahili as we slowed to pull to the side of the road in front of a dark wooden storefront. When I asked what was happening, my heart sank to learn that we had another flat tire—and no jack with which to put on the spare! Our driver quickly exited the car and disappeared down the dark village street, soon to return with several men. All passengers were required to get out of the car while the villagers lifted up the rear end so that the tire could be changed! I felt quite uncomfortable standing alongside the road in the dark, remote village, the only Westerner for miles around and far from any law enforcement. While the Kenyans I had met so far were kind and gracious, there was always the possibility that, at this time of night, a few young men, having had too much to drink, might try to take advantage of a lone Muzungu. As I experienced that sense of unease, I felt a deep appreciation for the prayers that I knew were being offered for me back home. In a few minutes, I breathed a sigh of relief when the tire was finally changed. We quickly climbed into the car and were on our way again toward Kisii, still miles away.

Our renewed journey was brief, however, for within one-half hour, we were forced to pull to the side of the road yet again because the engine was over-heating, as it had earlier that day. As the driver got out to fetch the plastic bottles of water he had wisely stored in the “boot” that morning, I heard the sound of a strong voice coming from near a hut in the darkness about 50 yards to my left. Despite my utter weariness and growing hunger, my spirit was lifted as the familiar melody, “Rock of Ages,” wafted through the darkness from an unknown voice singing powerfully in Kiswahili. I felt as if we were surrounded by unseen angels and that God had sent a messenger to remind us that we were not forsaken after all! When Dr. Githiga found two small South Beach chocolate bars in his briefcase, I gratefully gobbled one up, washing it down with warm water. After the radiator was topped off with water and the engine cooled, we travelled on through the darkness, navigating around potholes and over speed bumps, finally arriving at our hotel in Kisii at 10:00 P.M., dirty, dusty and exhausted. Too tired to shower, I fell asleep on top of the bed covers, barely aware of the incessant street noise just outside my window.

Despite the many difficulties of the first day, the conference in Kisii was a great success. Not only did Dr. Githiga consecrate three bishops during the conference, but also the fellowship of ANCCI grew and even extended its roots into nearby Tanzania. In addition, another Regional Coordinator was appointed for the University. Finally, we learned of a plan we wish to support, wherein farm land will be rented from the neighbouring Massai tribe and crops grown and sold in order to support the needy pastors of the surrounding area.

On the Sunday morning after the conference, we returned for the third and final time to the remote mountain church in the Kisii Highlands, for the regular Sunday morning worship service, where Dr. Githiga and I were invited to be the guest speakers. The church was packed with men, women and children of all ages, joyfully worshipping God in rhythmic praise and worship music. Clearly, the local, village church is a lifeline for the impoverished, toiling, yet deeply-spiritual people of the remote mountains of western Kenya. Dr. Githiga was overjoyed to see the children happily and enthusiastically taking part in the praise and worship music. “They are learning to enjoy God,” he said, smiling brightly.

After we had spoken, more than a dozen people came forward, so that we might lay our hands on them in prayer for the sick, many of them young mothers carrying babies and small children, some hot with fever. Then, a middle-aged woman who has never been able to walk was carried forward by several men for healing prayer. As I looked down upon her broken, crippled body, her tiny, atrophied legs folded under her in the small plastic lawn chair in which she had been brought forward, I thought of the many miraculous “healings” that are a routine part of the glitzy performances of the televangelists. I wondered what they would do with this woman—for this was no show. There were no television cameras present and no operators standing by to take donations. Here was simply a remote mountain church in the middle of nowhere—with a dirt floor and clay walls, no electricity, and an outhouse for a toilet—filled with impoverished worshippers who earned their meagre livings picking tea or farming their small plots of land. I laid my hands on this woman and tenderly caressed her with all the love in my heart. I simply prayed that God would do what was best for her in his own time. I could do no more.

We left the church in the Kisii Highlands in time to visit another smaller church in the mountains several miles away. Along the way, we stopped for a short visit at an orphanage and day school sponsored by Bishop Gwako and his network of churches, where we met the director and one of the teachers, as well as several of the children living there. We were unable to meet all the children, however, for some had run away in terror to hide when they saw the tall Mzungu approaching. Because they are in need of textbooks and other basic supplies, we resolved to offer what assistance we could to this tiny orphanage in the remote mountains, one of the many worthwhile ministries unknown and overlooked by the large, worldwide Christian charity organizations.

We left the orphanage and soon arrived at an outdoor church, covered by a thatch awning and surrounded by the lush greenery of maize, banana plants and tea crops. Parking the car some distance away, we could hear the sound of singing and the rasping voice of the praise and worship leader, joyously cheering on the congregation through a screeching microphone and speaker system long past its prime. We were heartily welcomed by the appreciative congregation, who had been patiently waiting for us several hours already. Because it was a special occasion, with “distinguished” visitors present from the far away United States of America, the church elders came forward one-by-one to greet us and share a few words of welcome. As we sat at the front of the small congregation, I began to feel exceptionally tired and thirsty, for the gruelling schedule of the past two weeks was beginning to take its toll on me. Yet, I silently asked God to give me strength, so that I could give all I had to these lovely people who had waited so patiently and eagerly to hear the messages we would bring. When I stood to speak, noticing the lush vegetation that surrounded us, I drew smiles of delight from my listeners when I remarked that the lovely mountain setting reminded me of the Garden of Eden.

After the service, we were invited to a nearby home a short walk away, where we visited with several of the local pastors and ate generous portions of rice, stew, and chipati, accompanied by an excellent chai. Like many of the homes in western Kenya, our host’s home was constructed of thick clay walls and floor and covered by a tin roof.

A similar building with a thatch roof stood alongside and served as a kitchen. Another of the thatch-roofed houses nearby served as an orphanage for several small children. As I was taking a few quick photos of the cluster of homes in the tiny neighbourhood,

I saw an elderly woman a short distance away, standing with a small child outside her modest clay home. Noting her eyes were dim with cataracts, I drew close and asked permission to take a “snap” (photo) of her home. She smiled and graciously consented.

After our meal and a short discussion about ANCCI, we returned to Kissi, arriving at our hotel near sunset. There we were met by Bishop William Githiga, a high-ranking official in Kenya’s prison system, who would drive us back to Nairobi the following day, where we would spend our last night in Kenya in residential quarters for government officials.

Return to Nairobi

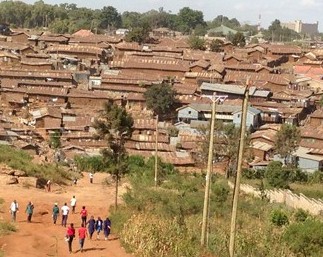

On Monday morning, we began a day-long journey to Nairobi, from where we would depart for the United States. After spending the night in the gated and guarded residential compound for government officials and their families, we spent our final day in Kenya in noisy, congested Nairobi. After a short visit to a local market to shop for souvenirs for loved ones back home, I asked Gabriel, our driver, to take us to Kibera, the largest urban slum in Africa, located near the city centre of Nairobi. Kibera is populated by perhaps one million people who live in 12' x 12' mud-walled shacks, often housing eight or more inhabitants, without electricity or running water. Surprisingly, the slum was only a short distance from the gated residential compound where we had spent the night. Our driver advised against entering the slum for safety reasons, so we scanned its sprawling squalor from a nearby hillside. Because of the discontent that accompanies abject poverty, Kibera is a prime target for Al-Shabaab, the Somali branch of radical Islam that seeks to destabilize neighbouring Kenya.

After what seemed a long day of checking my watch—for I was anxious to return home now that our mission in Kenya was completed—we finally left for the airport to catch our midnight flight to London and then home. As we had found so commonplace in developing Kenya, our route to the airport was blocked by late night construction, so that we were forced to detour through the infamous Kibera slum. As we slowly passed through the darkened narrow dirt streets lined with ramshackle structures of mud, rusty tin and rotting wood, faces peered at us through the darkness, barely visible in the dim light of intermittent kerosene lanterns. Slowly passing a dirty block building, I could see through its dingy, smutty window a dimly-lit room, where men aimlessly sat around card tables, while others slumped over a billiards table. Peering through the dirt, ding and darkness, I felt as if I were gazing deep into Dante’s Purgatory. We slowly passed through sewer water that covered half the road, and then we gradually left the slum behind, driving onto a paved road not far from the city centre. The sidewalks, streetlights and bright storefronts that lit up the night seemed to suggest that the abject poverty of the sprawling slum was only a rumour, something to be put out of mind and forgotten.

We finally arrived at the airport and began the difficult process of getting ourselves and our luggage to the ticket counter where we would receive our boarding passes. Near midnight, after passing through five baggage checks and a body scanner, we were finally allowed to board a British Airways 747, aboard which we would fly a sleepless night to London and finally home. As God’s grace would have it, I sat beside a young missionary, bound for her hometown in south Texas, where she hoped to raise money to return to Kenya, where she presently lives and works as a Bible teacher. In her travel bag, she carried a precious collection of textbooks covering a variety of theological and biblical subjects. During our layover in London, Dr. Githiga and I were able to review these texts and, having found them both relatively inexpensive and of high quality, we determined to use several of them in our own seminary program.

After four hours at London’s Heathrow Airport, we boarded another British Airways jumbo jet for home. After the lengthy process of passing through U.S. Customs in Dallas, Dr. Githiga and I parted company, he to return to Amarillo, Texas, and me to Jackson, Mississippi. After 41 hours without sleep, I was met at the airport by my wife Sara, all too happy to be back home after what had been one of the greatest and one of the most difficult experiences of my life.